North Berwick Witch Trials 1590-91

One of the most famous, notorious and complicated witchcraft accusations are those of associated with North Berwick.

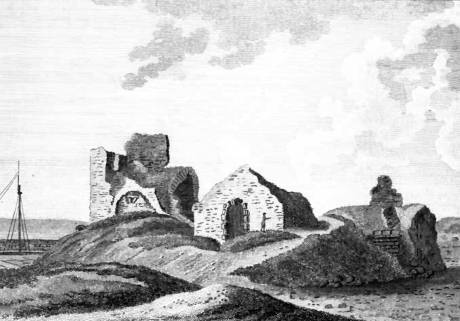

North Berwick is a pleasant seaside town on the south coast of the Firth of Forth in East Lothian in the south-east of Scotland. The main incident reportedly took place among the ruins of the old parish church by the shore, a part of which can still be visited on the way to the Seabird Centre (the church was a ruin even at the time of the trial, having been partly washed away in a storm).

This episode involved members of society from the lowest to the highest, from the king of the time, James VI, to maidservants, and many in between: peasants, the wives of advocates and Edinburgh burgesses, and finally a Scottish Earl. Although quite early in the cycle of witchcraft trials, it involves many elements that were to appear repeatedly in later accusations and James VI wrote his influential work Daemonologie based on this episode and a similar case in Denmark.

GEILLIS DUNCAN

Geillis (or Gelie in documents) Duncan was a maidservant in the service of David Seaton, who was a baillie depute in the East Lothian village of Tranent.

Seaton had become aware that Geillis was often absent from his house without explanation during the night and became suspicious of her behaviour; he confronted her and then interrogated her.

Why he thought she might be involved in witchcraft, and not just fornication or adultery, is not clear, although it may have been because Geillis had a reputation as a charmer: a wise woman or healer. Seaton would have, of course, as a churchgoer, been aware of concerns about malefice and witchcraft during the turbulent period when the reformed church was being established in Scotland after 1560.

Whatever the cause, Seaton had Geillis arrested and she was imprisoned in the tolbooth of Haddington, although he had not sought permission from the authorities.

Geillis denied any wrongdoing. Poor Geillis was then tortured – a not uncommon method for extracting a confession in the sixteenth century – and pilliwinks were used on her, crushing her fingers, and she was also tortured by ‘binding or winching her head with a cord or rope’.

Seaton also had her body searched for a Devil’s mark by a local pricker, looking for a blemish on her skin where she felt no pain, and such a mark was found on her neck.

Perhaps, not surprisingly, Geillis then confessed; a long and detailed testimony. She told them she had made a pact with the Devil, and that she had attended meetings with other witches at several places, of which the old kirk of North Berwick was one.

Those she implicated included Agnes Sampson from Haddington, Bessie Thomson from Edinburgh, Dr John Fian from Prestonpans, Janet Stratton, Donald Robson, Ritchie Graham, as well as Euphame MacCalzean and Barbara Napier, both of whom were well-to-do ladies from Edinburgh. These two were related to Thomas MacCalzean, Lord Cliftonhall, Provost of Edinburgh and Senator of the College of Justice. Indeed, Euphame was his daughter and heir, yet despite her high status, she was to suffer a most horrible death.

Geillis was held from December 1590 until June 1591 and was repeatedly questioned before finally being executed by being strangled and burned. Before she died, however, she claimed that all the things she had said about her co-accused were lies; this was however too late to influence their fate. Bessie Thomson was also executed.

JOHN FIAN

John Fian from Prestonpans, also in East Lothian, was also soon in custody, having been arrested in December 1590, although he was to die quite soon after, in late January of the following year.

Much of the information about John Fian and his co-accused comes from a pamphlet called ‘Newes from Scotland’, which was published in London in 1591 and claimed to detail the ‘damnable life of Doctor Fian, a notable sorcerer, who was burned at Edenbrough in January last’. The author remained anonymous, although was most likely at least present at the trials, but it seems likely the accounts were heavily edited and sensationalised to make the pamphlet more saleable. Indeed, the veracity of the document may be questioned at many points.

Dr John Fian appears to have been a character of some note: among his many other claimed misdemeanours was a confession that he had committed fornication with some thirty-two different women. He also had a number of aliases, such as John Fean, John Cunningham, John Sibbet and, of course, Dr Fian.

Fian was the schoolmaster at Prestonpans, although he also taught in nearby Tranent, where he may have first come into contact with Geillis Duncan. Like Geillis, Fian was tortured before he confessed by being partially throttled and later, when he refused to co-operate further, his feet and legs were crushed by the use of the boot.

Fian repented and escaped from prison but he was recaptured and mistreated further, by having his fingernails ripped out and nails hammered into the tips of his fingers. Before his execution, Fian retracted his confessions, claiming – quite reasonably – they had been extracted by torture. It made no difference, of course, and he was strangled and burned, also on Castle Hill in Edinburgh.

One of the most absurd tales, which would be comic if the circumstances surrounding it were not so terrible, was a spell Fian was supposed to have cast that went badly wrong. Fian desired the sister of one of his students and tried to use love magic to attract her. To do this, however, he needed hairs from the object of his fancy and he asked the lady’s brother to procure these for him. The student, however, believing something was amiss, went to his mother with the request and the mother substituted three hairs from the udder of a cow. Fian worked his spell using the hairs and was then chased around by the love struck cow.

More seriously Fian also confessed that he was present at all the witches’ meetings, including at North Berwick, when the Devil was always present. As a literate man, he was the ‘clerk’ and took the diabolic oaths of true service to the Devil from those present. He also described how candles, sermons, prayers and preaching were all used in a Satanic inversion of the Christian service. The group had, among other things, ruined crops, destroyed livestock, killed men and caused storms, including one intended to drown James VI and Anne of Denmark when they returned to Scotland. This latter action was of course, one of treason, although he later went back on this confession.

AGNES SAMPSON

A third accused was the widow Agnes Sampson (or Sampsoune), who was from the hamlet of Nether Keith, by the grand mansion of Keith Marischal, near the village of Humbie in East Lothian.

In 1589 she was questioned by the Haddington synod, but from the turn of the following year she was interrogated by no less a person than James VI at Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh.

His interest may have been partly fuelled by a case in Denmark the previous year, when six women were accused of witchcraft and trying to prevent Anne, James’s wife, from reaching Scotland.

Initially, Agnes refused to confess but, like the others, she was tortured and searched by a witch pricker, and went on to name others she claimed were involved: Katharine Gray, David Steel and Janet Campbell, as well as Barbara Napier and Euphame MacCalzean; in the end fifty-nine other people were named.

Indeed, she went on to tell the king that more than two-hundred witches were involved. Her crimes, she said, included attending covens and sabbats, using magical charms, and being involved in trying to murder the king and his bride.

Like Geillis Duncan, Agnes was known as a healer, or a charmer as it was called in Scotland, and her clients included both the poor and ordinary folk and lords, lairds and their womenfolk, from places such as North Berwick, Dirleton, Preston(pans) and Dalkeith.

As well as attempting to cure illnesses (although not always successfully), she also helped reduced the pain of childbirth. Agnes was paid for her work and claimed that she had learned what she knew from her father. Initially, Agnes only acknowledged her healing and charming, such as divination and love magic, rejecting the Satanic nature of her work, but over the course of a week she confessed to witchcraft. It is entirely possible that she was tortured during this time…

After her husband had died, she claimed that the Devil had come to her, and she had followed him because of poverty and revenge. A Devil’s mark was found on her right knee, although she said that she had thought that the injured spot had been received from one of her children while they were in bed. She claimed that she invoked the Devil when healing folk, called him ‘Elva’ or ‘Eloa’, and he appeared to her in the form of a dog.

Agnes described, in colourful if not entirely credible detail, how on Halloween (All Hallow’s Eve or the 31 October) of 1590, some two-hundred witches had journeyed across the sea by sieve to the old kirk at North Berwick, bringing fine wine and ale with them.

Here they met the Devil and there was a huge party with singing and dancing – indeed, she claimed that Geillis Duncan had played on a Jew’s Harp (a small musical instrument held between the teeth and plucked with the finger). She also said that the witches all had to kiss the Devil’s bottom, and they performed an inversion of the Christian service, with prayers and black candles.

At the ceremony, one of eleven that she described, the Devil had baptised a cat, which he then threw into the sea. This spell was to raise a storm with which to sink the ships conveying James VI and Anne of Denmark back to Scotland, the Devil saying, ‘the king is the greatest enemy he has in the world’ (according to ‘Newes from Scotland’). James had indeed come through rough weather, although this was hardly unusual in the North Sea at the end of October. His ship survived the voyage but a sister vessel, carrying his new queen’s treasure and valuables, was lost.

Up to this point it is thought that James had actually remained somewhat sceptical, even saying (again from ‘Newes from Scotland’), ‘they [the accused] were all extreme liars’. Agnes then apparently took James aside and whispered in his ear the exact words that passed between James and Anne on their wedding night. This is an interesting admission by her, not least that it would almost certainly get her executed…

Her confession did not stop there. She described how they used wax figures and animals, and invoked a spirit in the form of a white stag. One spell included collecting the venom from a toad, which had also been intended to harm the king, although she also needed to use an item of the king’s clothing or something he owned. Apparently one of the king’s servants, John Kers, was asked to help them but, perhaps luckily for the king, he refused. She also claimed that she used parts of corpses in her spells.

When the unfortunate Agnes had no more to confess, on 28 January 1591 she was strangled and then burnt. At the end, it is said she was penitent and prayed to God for salvation.

BARBARA NAPIER

As mentioned before, Barbara Napier and Euphame MacCalzean were implicated by others, although their part should have been minor. Barbara Napier was married to Archibald Douglas and her brother was a rich Edinburgh burgess so she was wealthy enough to employ a defence counsel.

The accusations against her were principally that she had consulted witches, not that she was a witch herself, and had used the services of Agnes Sampson and Ritchie Graham. She had procured the assistance and advice of Agnes to help Jean Lyon, wife of the eighth Earl of Angus, who was suffering vomiting during her pregnancy.

It seems that Barbara acted as an intermediary as it was Jean Lyon, the Countess of Angus, who later on got Barbara to arrange with Agnes a ritual using image magic to cause the death of her husband the Earl. By whatever cause, the Earl died in August 1588.

Barbara also consulted Ritchie Graham to help cure her son of an illness and reportedly sent him a ring to enchant. The kind of accusations levelled against Barbara were quite typical – curing illness, influencing behaviours and outcomes, protection against malice, attempting to cause death – but because of her dealings with Agnes Sampson – which therefore implied an association with the North Berwick conspiracy – she was, like the others, charged with treason.

Barbara was tried in May 1591, and she was represented by John Moscrop and John Russell, who were employed to argue her defence.

They objected to some proposed members of the jury: David Seaton, who was connected to events in Barbara’s indictment. John Seaton, who was the brother of David Seaton of Tranent who had started the first accusation against Geillis Duncan. And thirdly John Douglas, who had been a hostile witness against Barbara.

Barbara pled guilty to the charges of seeking help from witches but denied any involvement in treasonable plotting. She was initially found guilty of consulting but not guilty of treason. In order to delay her execution, Barbara also claimed that she was pregnant.

James VI, however, was not happy with this verdict and personally addressed the jury on points of law. He also issued a warrant charging them with wilful error. The jury gathered for a second time on 9 June and this time issued a guilty verdict on the charge of treason, claiming ignorant, rather than wilful, error.

EUPHAME MacCALZEAN

The charges against Euphame MacCalzean were more extensive than Barbara’s: twenty-eight items including magical rituals associated with efforts to cause the death of James VI and prevent Queen Anne arriving in Scotland.

Other charges were more personal and related to her unhappy marriage and her dislike of her husband, Patrick MacCalzean or Moscrop, an advocate, who changed his name from Moscrop to MacCalzean when they were married.

Euphame was the illegitimate daughter (she was later legitimised) of Thomas MacCalzean, Lord Cliftonhall, also an advocate, who was a Senator in the Court of Justice. She appears to have made various efforts to rid herself of her husband, consulting several witches and carrying out a number of procedures which involved enchanting his clothes and, the ever popular, use of poison.

The victim, Patrick, appears to have suffered episodes of illness and eventually left the country to seek a cure for his health – or just to get away from Euphame. On his return, she again requested help from an Irish woman, Catherine Campbell, who lived in the Canongate (now part of the Royal Mile of Edinburgh), which involved sprinkling his doublet with blood thereby enchanting it. Patrick once again fell seriously ill for some months.

As well as trying to rid herself of Patrick, Euphame used magic to help find a new, and younger, husband: Joseph Douglas, laird of Pumpherston, an estate to the east of Livingston in West Lothian.

Euphame tried using love magic and sent the object of her desire several items of jewellery, which included a neck chain, belt chains, a ring and an emerald. She also tried to first injure and then, later, convince Joseph’s fiancee that he was unsuitable for marriage because he was suffering from a venereal disease, using her servant Janet Drummond to carry out the task. When none of the above were successful, Euphame resorted to attempting to poison Joseph. She was also keen to get her gifts of jewellery returned as her extravagance had not paid dividends!

She was further accused of causing death by witchcraft of her nephew, her father-in-law, a young girl and several other people. Most of these other deaths were caused using enchanted cloths and clothing or image magic: Agnes Sampson was involved in using an image of Euphame’s father-in-law and was consulted by Euphame on several occasions. Euphame was also accused of attending the convention at North Berwick and being involved in the attempts to sink the king’s ship, by conjuring cats and throwing them into the sea.

Euphame’s trial was held in June 1591, when she was defended by John Moscrop, David Ogilvie and John Russell, two of whom had defended Barbara Napier. She was found guilty on several points of her dittay notably: consulting with several witches including Agnes Sampson and Catherine Campbell, causing the death of her nephew, attempted poisoning of Joseph Douglas, using rituals to reduce the pain of childbirth, using image magic and importantly of attending the convention at North Berwick with Agnes Sampson, John Fian and others, and seeking the treasonable destruction of the king.

Interestingly, she was found not guilty of trying to murder her husband. Euphame was ordered to be ‘burned quick and forfeit’. This meant that Euphame was not given the benefit of being strangled before being burned – she was burned alive.

FRANCIS STEWART, FIFTH EARL OF BOTHWELL

Francis Stewart, fifth earl of Bothwell, was the final player in the convoluted and complex North Berwick conspiracy.

As early as April 1591 Bothwell had been accused of conspiring with others, notably Ritchie Graham, but it was not until Barbara Napier’s verdict that Bothwell was imprisoned. It was Ritchie Graham who had given his inquisitors details about Bothwell’s involvement and claimed that he had been the main instigator of the plot. Others had also named him, including Geillis Duncan and Agnes Sampson.

Bothwell was James’s cousin, a nephew of James Hepburn, fourth earl of Bothwell, who had been Mary Queen of Scots’, somewhat controversial, third husband.

During the months before James VI left for Denmark, Bothwell had been involved in a rebellion against the king in the south, partly in support of the rebelling Catholic nobles in the north. James had a number of political and religious issues to deal with at this time, notably controlling the successors to the crown the Lennox-Stewarts and the Hamiltons, dealing with Catholic nobles such as Huntly, and establishing supremacy over the argumentative kirk.

Bothwell was promoted to membership of the Council of Regency, a high status position which gave him much power and influence; indeed he was appointed admiral which gave him some responsibility and control over the Danish voyage. It is clear that James VI would later feel threatened by Bothwell’s power and influence; however it was the king himself who promoted and rewarded Bothwell, whose motives were always self serving rather than altruistic.

In June 1591 Bothwell was ordered to be released but on condition that he was to be banished from the kingdom. Bothwell broke out of prison and fled to Caithness; resulting in him being declared traitor and having his property forfeited.

For the next two years he evaded recapture but ultimately, in August 1593, he stood trial in Edinburgh. His indictment listed several meetings with Ritchie Graham, where Graham was requested to consult with the spirits about Bothwell’s relationship with James VI. He was also accused of meeting Agnes Sampson and others associated with the North Berwick group. On 10 August 1593 Bothwell was acquitted of all the accusations contained in the dittay, and importantly of the accusation of treason and attempting to kill the king.

Perhaps it was James’ own paranoia that developed the North Berwick case from a few ordinary men and women who had used magical rituals for healing or in the hope of manipulating fate, to a large number of conspirators led by an earl of the realm, whose primary target was the destruction of the king. Perhaps Bothwell was someone who was capable of developing such a dangerous plan, but to attempt something so extreme and to involve so many people would seem risky; too many opportunities for mistakes, for leaks, and for people to turn informer.

Torture was used against several of those thought to be involved: Duncan, Sampson and Fian. There is no doubt, also, that for whatever reasons, others confessed to details and gave statements that were either directly, or interpreted as, linked to Bothwell. Ritchie Graham, interestingly, was offered immunity by Bothwell’s enemies and protection if he gave evidence against Bothwell. Graham was eventually executed in February 1592, while Bothwell was on the run as an outlaw.

Indeed, by this time James’s actions were being criticised. Parliament met in Edinburgh and noted that public opinion was ‘strongly against the king’ for his complicity in the murder of the Bonnie Earl of Moray; he also had further pressures from the presbyterian wing of the kirk, led by Andrew Melville.

By December of that year, Bothwell took advantage of the tension and made a public statement about his innocence, blaming the whole thing on James VI’s Chancellor, Sir John Maitland of Thirlestane, and also claiming that those who had been previously executed were also innocent.

By 1593 Bothwell managed to effectively take control of James VI’s government, not a easy task for someone who was declared an outlaw and liable to be taken prisoner at any point. It was a result of this political manoeuvring that Bothwell managed to bounce James into holding a trial to clear his name and restore his estates; a trial that Bothwell must have been pretty sure would deliver a verdict in his favour. The jury of two earls, seven lords and eight barons found him not guilty and declared that Ritchie Graham had been blackmailed into accusing Bothwell of witchcraft and conspiracy. Bothwell was received with ‘great joy’ by the people of Edinburgh, and the king was, for a time, dominated by him.

Bothwell’s hour of triumph was short-lived, however, and by September 1593 he was again banished from Edinburgh under pain of treason. Bothwell’s arrogance had allowed James to build support against him amongst the rest of the nobility and by 1595 Bothwell was again in trouble.

Having previously been a religious vacillator, in early 1595 he was excommunicated by the Edinburgh presbytery for joining with Catholics, despite his claim that he had been forced to do so because he had lost his estates. His brother had been hanged, his estates were divided up and granted to various other nobles, and he was finally exiled, this time for good, in April 1595. He eventually died in 1612, in Italy where, it seems, he had developed a reputation for necromancy.

By this time Queen Anne had given birth to a male child – Henry. James VI had held off the threats from the northern Catholics and he had finally seen the last of the North Berwick plotters. At the same time as managing affairs of state and threats to his security, James had compiled his book on witchcraft Daemonologie, which was published in 1597. The following year a number of accusations surfaced in Aberdeenshire about witchcraft and witches. This time, however, the king was not the target.

© Martin Coventry 2017

text from Scotland's Wicked Witches